One day in August 1996, I took a deep breath and walked into a Borders Bookstore in a nondescript shopping mall in Wayne, New Jersey, twenty miles southeast of New York City, and introduced myself to the store’s ‘community events coordinator.’ I told her of this idea I had of starting a weekly dialogue group featuring a version of the Socratic method in which me and my fellow inquirers and I would thoughtfully explore those philosophical questions that most weighed on our minds and hearts. I certainly had my fair share of pressing existential concerns and conundrums, and I much desired the considered perspectives of others in gaining some enlightenment on them. What is more, it seemed to me that American society itself was in a state of crisis that much of its citizenry chose not to recognise, yet that demanded a response.

Some years later, in Socrates Café: A Fresh Taste of Philosophy (2001) I relate that I decided to hold my first Socrates Café dialogue group as one modest effort to combat in the United States “what I perceived as an extreme and pervasive self-absorption and intolerance among people, coupled with a lack of any sense that they were their brothers’ and sisters’ keeper” (p. 130). But my ends were in fact more positive, namely to create a type of dialogical inquiry group, in a public setting, that created bonds of empathy and understanding among participants. Ideally, this in turn would prompt contributors to become more committed to one another; to do their utmost to help one another discover, cultivate and contribute those talents that would lead to a singular type of excellence. To my mind, the pursuit of the noble, the good, of all-around excellence – what the Greeks of antiquity called arête – can best be accomplished within a society with a type of openness that seeks ever to widen the circle of inclusiveness.

To make even modest inroads in achieving such a lofty goal, however, it seemed incumbent to have our dialogues driven by a method that would not so much force but inspire participants to challenge their own, and one another’s, dogma; so that any desultory habits that allowed for complacency in thought would be supplanted by ones that inspired both our critical acumen and imaginative vision. It further seemed to me that what political theorist Dana Villa said of the Greeks of the Athenian polis in which the historical Socrates resided in the 5th century B.C. could also be said of many Americans of my era. Namely, the citizenry in both societies posed a considerable challenge to the formation of such communities of inquiry, “not because they were more dogmatic than other peoples […], but because they were the most active of peoples, the most restless and driven” (2001, p. 4).

The qualities of being restless and driven are neither inherently positive nor negative, but whether they are channeled in positive or negative ways seemed to me to hinge at least in part on whether we take the time to examine ourselves and consider how best to harness our energies. Further, it is wise to contemplate the type or types of moral code(s) we might strive to cultivate to advance humanistic ends. To this end, much as Villa’s imagines her version of the historical Socrates to do, I planned to disseminate a type of Socratic inquiry via Socrates Café which was aimed at engaging “fellow citizens on the question of how one should live” (2001, p. 5).

But the aim was by no means primarily or solely to transform others; rather, it was to serve as a means better to understand, articulate, explore, and indeed further discover my own moral code, to gain a keener sense of whether the values I professed were aligned with the way I actually lived; and to determine whether my code and my world view were in need of alteration or even of considerable overhaul. To realize this, I needed others. Margaret Betz Hull, in The Hidden Philosophy of Hannah Arendt (2002), notes that Arendt, a political theorist renowned for her studies on the problematic nature of power, identifies in her version of the historical Socrates what “she believes to be a unique respect for doxa, to each individual’s own opening to the world” (Hull, 2002, p. 107).

Arendt explains that ‘the world opens up differently to every man, according to his position in it’ but that there is a ‘sameness of the world, its commonness’ which ‘resides in the fact that the same world opens up to everyone and despite all differences between men and their positions in the world – and consequently their doxai (opinions) – ‘both you and I are human.’ […]

Arendt argues that Socrates’ voluntary involvement with the doxai of others reveals an interdependence to the formation of opinions: ‘…just as nobody can know beforehand the other’s doxa, so nobody can know by himself and without further effort the inherent truth of his own opinion’ […] Present here is also a taste of Arendt’s notion that the formation of the self is not possible in isolation; others are needed, as in this case, for the expression and development of my unique doxa. (2002, p. 108)

I also subscribe to the belief that I can only further, and prospectively better, sculpt myself with the dedicated help of others. This requires that I continually seek forms of encounter with others in which I can come to a more acute understanding of what my words and deeds and ideals, and the value system on which they are based, amount to. I deemed it essential regularly to hold philosophically-grounded inquiries featuring a modernized version of the Socratic method. These took place in public spaces with diverse others, in order best to realize this.

In my estimation, the ultimate end of Socratic inquiry is to engage in a type of discursive, methodically-based deliberative exchange that contributes to democratic renewal and even upheaval. This view is based on a notion of self in which the individual and society are not at opposite ends of a continuum, but are interlaced, requiring a dual nurturing of both if greater individual autonomy is to be coupled with a developing social conscience for the realization of democratic ends.

Additionally, in my view, if one divorces Socratic ideals and their integral political dimension from the ideal Socratic setting – namely, the public marketplace, what the Greeks called the agora – one diminishes the capacity of Socratic inquiry to advance deliberative democracy. I hence felt that a democratic citizenry needed continually to cultivate what political science scholar Dana Villa describes in Socratic Citizenship (2001) as a critical-skeptical bent, in order to practice constructive dissidence, with the end of cultivating forms of individual, communal and societal excellence in which citizens develop a successively greater commitment to achieving arête.

Villa characterizes the ideal form of democratic citizenship as necessarily Socratic in its essence; to him, this is tantamount to placing value on the form of “conscientious, moderately alienated citizenship” that he argues is modeled by the historical Socrates. This kind of citizenship is one that is “critical in orientation and dissident in practice,” and is “cause-based, group-related, and service-oriented” (p. 2). I am not sure, though, that such conscientious citizenship is always one in which we are moderately alienated – depending on the time and clime, one might not feel alienated at all, while at others, one might feel extremely so.

Be that as it may, I began Socrates Café in part because of a great sense of alienation not just, or not principally, from the processes of government. Instead, I felt my greatest sense of alienation as being from my fellow ‘ordinary’ citizens in most deliberative spheres in the public realm that were supposed to be accessible to us, including places such as coffee houses, where rarely if ever did citizens gather with anyone whom they did not know to engage in thoughtful discourse.

Socrates Café did seem to me to fit Villa’s ‘Socratic’ criteria of being cause-based, group-related, and service-oriented; even if not directly or overtly political; and even or especially if cultivating greater individual autonomy was a primary result. Like Villa, I tended to agree, when I first started Socrates Café, that such inquiry is not “a directly political exercise”, though it “does have political implications” (2001, p. 4); among other reasons because the insights gained from such inquiry can be one principal determinant of our political positions and dispositions, and hence impact our civic involvement or lack thereof.

However, it may be a more direct political exercise than it ostensibly appears. Charles Taylor, noted Canadian political philosopher, professor and politician – his inquiries into democratic recognition, identity and difference have gained notoriety in both academic and lay circles – maintains in essays such as “The Politics of Recognition” (1994) that contemporary open societies must go to great lengths to enfranchise members of all the cultures of which it is comprised.

This is not to say that people’s opinions are equally or intrinsically of the same worth; rather, the distinguishing trait of a democracy is that such worth can only be gauged as its members take part together, on an equal footing, in the deliberative process, subjecting their views to critical scrutiny and empathic immersion by diverse others. My aim was for Socrates Café to be a deliberative dialogue group that interrogated varying views with a method that demanded such scrutiny and immersion. As such, Socrates Café could possibly make a fruitful contribution to this end of fomenting deliberative democracy and to the extent that it does make such a contribution, perhaps it is in fact a direct form of political exercise, albeit a subtle form, because of its predominantly philosophical bent.

Princeton University philosopher Cornel West in Democracy Matters: Winning the Fight Against Imperialism (2004) stresses the importance of Socratic inquiry for overall democratic vitality. West argues that in order to strengthen and evolve democracy today, we must embrace “Socratic commitment to questioning – questioning of ourselves, of authority, of dogma, of parochialism, and of fundamentalism” (p. 16). West believes that democracy cannot be had – much less revitalized – without this commitment, since Socratic questioning is what most successfully serves “to tease out those traditions” that might best “enable us to wrestle with difficult realities we often deny” (p. 41). One tradition that we needed ‘to tease out,’ in my view, was the Socratic tradition itself.

To West, bereft of the Socratic, the democratic tradition itself is susceptible to falling victim to those who would distort and pervert it for the pursuit of ends far removed from and counter to their original sublime function.

The Socratic commitment to questioning requires a relentless self-examination and critique of institutions of authority, motivated by an endless quest for intellectual integrity and moral consistency […] that unsettles, unnerves, and unhouses people from their uncritical sleepwalking […] (2004, p.16).

West maintains that Americans today are in dire need of recapturing “the deep democratic energy of this Socratic questioning in these times of rampant sophistry on the part of our political elites and their media pundits” (p. 17). West holds that the end of Socratic questioning is to develop “intellectual integrity, philosophic humility, and personal sincerity – all essential elements of our democratic armor for the fight against corrupt elite power” (2004, p. 208).

West additionally maintains that if American citizens are to perpetuate a rich, evolving democratic tradition, we need not just one Socrates among us, but a citizenry of Socrates which takes as its charge the challenge to expose “the specious reasoning that legitimated [the] quest for power and might” for its own sake by “seductive manipulations and lies” from the elite (p. 16). West further praises Socrates for his unprecedented “historic effort to unleash painful wisdom seeking – his midwifery of ideas and visions”. He avers that this Socratic work was “predicated on the capacity of all people […] to engage in a critique of and resistance to the corruptions of mind, soul, and society” (2004, p. 16).

Philosopher Martha Nussbaum – whose scholarly work often ties together ancient Greek philosophy with modern political thinking and ethics – suggests that individual and democratic evolution and revolution on a societal scale go hand in glove. In Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education (1997), Nussbaum asserts that the vibrancy of a democratic society hinges on its pervasive capacity to reason Socratically: “In order to foster a democracy that is reflective and deliberative […] that genuinely takes thought for the common good, we must produce citizens who have the Socratic capacity to reason about their beliefs” (p. 19).

Nussbaum goes on to maintain that a democracy cannot be in a healthy state “when people vote on the basis of sentiments they have absorbed from talk-radio and have never questioned. This failure to think critically produces a democracy in which people talk at one another but never have a genuine dialogue” (p. 19). To Nussbaum, the concomitant nurturing of individual autonomy and social conscience that is characterised by Socratic inquiry foments a more participatory and democratic society with a citizenry that “can genuinely reason together about a problem, not simply trade claims and counterclaims” (1997, p. 19).

John Dewey (1932) stresses in his Ethics that his variant of concomitant nurturing does not pit society against the individual, as if they are on opposite ends of a continuum, but demonstrates how the two are wholly entwined. As a consequence, it does not entail “a sacrifice of individuality,” much less connote “the submergence of what is distinctive, unique, in different human beings” (1932, p.383). To the contrary, it entails forms of sharing and participating that thrive on “diversification,” in which each citizen contributes “something distinctive from his own store of knowledge, ability, taste, while receiving at the same time elements of value contributed by others”. How does this come about?

To Dewey, only through “genuine conversation” in which “the ideas are corrected and changed by what others say; what is confirmed is not his previous notions, which may have been narrow and ill-informed, but his capacity to judge wisely” (p. 384). Such concomitant nurturing leads to “an expansion of experience,” to learning; and this is so even if one leaves an encounter more entrenched than ever in one’s particular view (p. 384). This is so because whenever there is “genuine mutual give and take,” it can be argued, one’s perspectives “are seen in a new light, deepened and extended in meaning, and there is the enjoyment of enlargement of experience, of growth of capacity” (p. 384).

The resulting “community of good” (p. 385) affords each member of society “the same opportunity for developing his capacities and playing his part” (p. 384). Such a perspective implies that all democratic citizens have both the right and the responsibility to sculpt our social practices, given that they are impacted by them. Working towards general social well-being, and greater individual self-actualisation, go in tandem, according to Dewey; life takes on richer significance when working integrally towards a shared and desired future (p. 385).

My Socrates Café endeavor represented, or was intended to represent, a modest attempt to revive the Socratic tradition for the types of ends spelled out by Dewey, West and Nussbaum, but also to utilize the types of means to which they allude. It was somewhat daunting that American culture was not inured to such inquiry. When I started my first Socrates Café group in that northern summer of 1996, even sympathizers told me that Americans were no longer capable of engaging one another in thoughtful discourse, certainly not in public settings where they did not know those taking part. If this was so, then it seemed to me that the ‘writing was on the wall,’ and that our democracy already was in the great decline that our more extreme doomsayers claimed. However, I did not think this negative portrayal was necessarily so; at the very least, it seemed worth verifying, or contradicting, this pessimistic outlook.

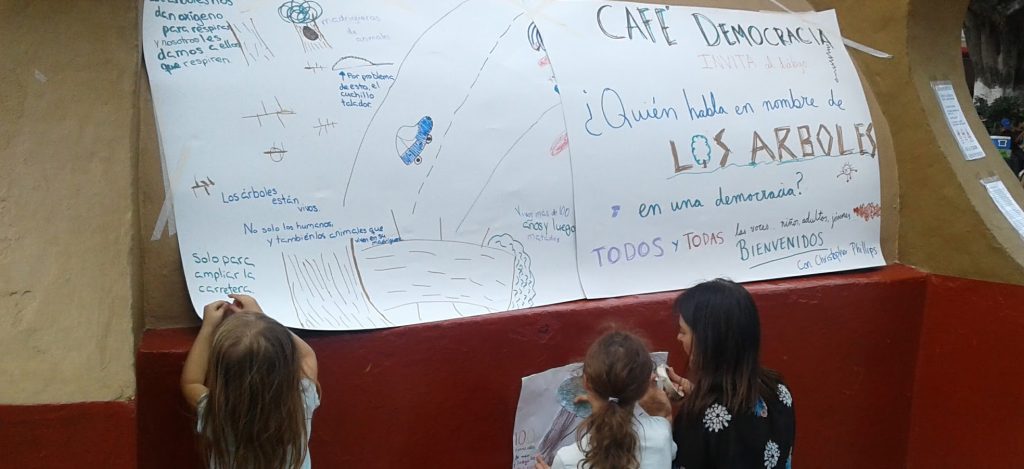

And so I my exhilarating journey and experiment with Socrates Cafe began. Over 21 years later, I believe I have indeed contradicted this gloomy outlook — or better put, the thousands of diverse people who take part regularly in our Socrates Cafes (and now Democracy Cafes as well) across the fruited plain and the world over do so.

copyright 2018